George Washington owned slaves. So did his wife, Martha. So did Adams, Monroe, Jefferson; the whole lot of them. Straight up slave owners. It wasn’t right, but that was the way things were, and were going to be for decades. Even though things are much better today, we still have a long way to go as we see how racism affects non-whites in the U.S.

George Washington owned slaves. So did his wife, Martha. So did Adams, Monroe, Jefferson; the whole lot of them. Straight up slave owners. It wasn’t right, but that was the way things were, and were going to be for decades. Even though things are much better today, we still have a long way to go as we see how racism affects non-whites in the U.S.

George Washington was a rich man.

In fact, you could say he was one of the 1% of his day. The vast majority of the men we like to call our “founding fathers” were also part of the 1% club, and those who weren’t part of that club were far from commoners.

Martha Washington owned approximately 180 slaves who, along with a bunch of land and even more money, were part of her endowment from her first husband. Martha’s slaves, according to law, could never be freed. George Washington, at any given time owned around 120 slaves.

Between the land that Martha brought to the marriage and that which was separately purchased by George, the Washingtons owned around 8000 acres spread over 5 farms in the Potomac River Valley. Approximately 4000 of those acres was in cultivation, growing crops. The rest was grazing land for cattle and other livestock.

Between the land that Martha brought to the marriage and that which was separately purchased by George, the Washingtons owned around 8000 acres spread over 5 farms in the Potomac River Valley. Approximately 4000 of those acres was in cultivation, growing crops. The rest was grazing land for cattle and other livestock.

Anyone who has ever farmed or ranched for living knows that farming and ranching are very labor intensive. Hell, if I owned that kind of operation I would have to hire a small crew of men and women to help me out, too. I simply cannot imagine trying to farm 4000 acres of cropland and having to do all of the work by hand or trailing an ox or a team of horses. When I farmed as a kid I would not have traded in my tractor for anything.

Anyone who has ever farmed or ranched for living knows that farming and ranching are very labor intensive. Hell, if I owned that kind of operation I would have to hire a small crew of men and women to help me out, too. I simply cannot imagine trying to farm 4000 acres of cropland and having to do all of the work by hand or trailing an ox or a team of horses. When I farmed as a kid I would not have traded in my tractor for anything.

I get it. George Washington would never have been able to maintain an operation of that size and make it profitable if he had to pay his slaves. To have paid 300 slaves would have cost him several small fortunes and he would have probably died broke.

I get it. George Washington would never have been able to maintain an operation of that size and make it profitable if he had to pay his slaves. To have paid 300 slaves would have cost him several small fortunes and he would have probably died broke.

Mount Vernon was organized like a small city-state–anything one needed could be produced on the plantation, save fabric for clothing. Crops to feed livestock, livestock for the table to feed the family, fruits and vegetables fresh from the garden, a greenhouse to grow citrus and fruits not indigenous to the Northeast, a blacksmith, livery, storerooms, a cobbler–virtually everything was produced on site.

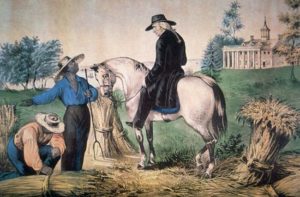

Some slaves worked in the fields, some tended livestock, and some were skilled craftsmen. Still others were house slaves who tended to the day-to-day needs of their masters George and Martha Washington.

I have been to Mount Vernon several times. I have also visited Jefferson’s home, Monticello, several times. I have been to James Madison’s home. In every case, the subject of slavery comes up. Tour guides rather sheepishly admit that all of these former presidents and founding fathers were slave owners. At Mount Vernon, they are also quick to point out that Washington freed his slaves (albeit, he only freed his own slaves, not Martha’s, and then not until 5 years after his death). Jefferson never freed his slaves.

In planning for my trip, when I saw that they were offering an Enslaved Peoples tour at Mount Vernon, I jumped at the chance to learn more about slave life on the plantation. It cost an extra 7 bucks but I figured it would be worth it.

I like to get to tourist destinations early so I booked the very first available tour on our visit, 10 a.m. We had arrived early enough to allow us some time to wander the grounds and the various outbuildings of Mount Vernon before the tour began. Shortly before 10 a.m., our little group gathered up at the appointed spot where shortly we were joined by our tour guide, a very nice young black woman.

We were led from the ellipse on the west side of the mansion down a path and into the formal vegetable and flower gardens which are adjacent to the greenhouse where citrus and other non-indigenous fruits, flowers, and vegetables were grown. We were told that Martha specifically directed that slave children were not to play in the garden–although the children of the cooks were allowed in as they knew enough about the gardens to be helping their parents gather and care for vegetables from the garden. Only the cooks, their children, a few trusted slaves and the Washingtons’ wealthy friends were allowed in the formal gardens.

We left the formal gardens through a gate and entered an area that would have provided the majority of the housing for the slaves. We were led into 2 bunk rooms, one for men and one for women, each containing up to 10 bunk beds and a large hearth. There was also the room that housed the fireplace that kept the greenhouse warm, the cobbler shop, and a couple of other rooms where the slaves worked.

We were repeatedly reminded that George Washington was troubled by slavery and that he was not entirely comfortable with it. Even though slaves were not allowed to marry, we were told that Washington recognized that slaves were forming family units and he would grant them permission to get married. When one of our group asked the guide exactly where those marriages were recognized, she responded, “they weren’t.”

We were also told that Washington allowed his slaves to work for themselves in their spare time or on their time off. They were allowed to, for example, own chickens, keep the eggs, plant and tend vegetable gardens, to keep a cow and to keep the milk and make cheese. We were also told that George Washington at times would even buy stuff from his slaves.

George Washington’s slaves worked from sun up to sun down Monday through Saturday. Everybody got Sunday off, including the slaves. If a slave had family on an adjoining plantation, he or she was permitted to walk to that plantation on his or her day off to visit as long as he or she was back at Mount Vernon and ready to work by sunup on Monday morning. Of course, slaves in transit were subject to being apprehended by other plantation owners and conscripted to work on their plantations.

George Washington’s slaves worked from sun up to sun down Monday through Saturday. Everybody got Sunday off, including the slaves. If a slave had family on an adjoining plantation, he or she was permitted to walk to that plantation on his or her day off to visit as long as he or she was back at Mount Vernon and ready to work by sunup on Monday morning. Of course, slaves in transit were subject to being apprehended by other plantation owners and conscripted to work on their plantations.

Oh, and our tour guide rarely ever spoke of these people as slaves. Rather, she referred to them as “enslaved people.” She also pointed out that black folks were not the only enslaved people, that there were many white folk who were “enslaved” but they were indentured servants; people who had their passage to America paid for by a wealthy person and who were expected to work for that person for a specified period of time until the indenture had been paid off and then were freed.

So see? It wasn’t just black folks. There were lots of folks who were enslaved. And George Washington wasn’t really that bad to his slaves. Right?

We were told that every enslaved person was given one set of clothes for the summer months, one set of clothes for the winter months, and one blanket for their bed. Pretty sweet, huh? I suppose with all that extra money they were making from Washington buying things from them they could always go out and buy an extra set of clothes or another blanket for their bad. Not likely.

Let’s rewind for a moment that whole “they could work for themselves in their free time” business. They worked from sun up to sundown 6 days a week. If they had family on a neighboring plantation, Sunday was the only day they had to reunite with that family. If you had chickens or a cow or a little vegetable garden exactly when was it that you were going to be able to attend to it? In the middle of the night? On your day off or do you let the garden or the animals go and visit with your family instead?

And then, almost as an asterisk, the guide told us that the enslaved people began breaking into the smokehouse and stealing meat because they weren’t getting enough to eat. Then, they started losing or breaking their tools they used to work with. The guide blamed this on the enslaved people hearing about slave uprisings on other plantations, because it couldn’t have had anything to do with the way George Washington treated his slaves because, as we previously learned, George Washington wasn’t really that bad to his slaves.

Our guide went to great lengths to tell us about George and Martha’s favorite house slaves: the 2 brothers who served as personal valets to George, their renowned chef Hercules, and Martha’s favorite slave in waiting, Oney Judge. We were told how they were dressed in the finest clothes and given the best treatment and that when George and Martha went to Philadelphia during George’s presidency, they were taken with them.

Pennsylvania at that time was a very forward looking state that abhorred slavery. Pennsylvania had a law that said that any slave who lived in Pennsylvania for 6 months could apply to the government for his or her freedom. George was president for 8 years, living in Philadelphia. So it stands to reason that George and Martha’s house slaves, their renowned chef and Martha’s favorite lady in waiting, obtained their freedom during that time, right? Wrong. George rotated his slaves every 5 and a half months or so to prevent them from obtaining the necessary 6 months of residency which would have enabled them to apply for freedom, and he started replacing black slaves with white indentured German slaves.

When Oney Judge learned that Martha intended to give her away as a wedding present, after serving the Washingtons and their guests dinner in Philadelphia one night, she quietly slipped out of the house and disappeared.

At the end of the tour, our guide told us that Washington was interviewed toward the end of his life and was asked if he had any major regrets. His reply was that he regretted not having done more to end slavery. She then told us that, for those who could stay, there would be a wreath laying and reading from slaves’ biographies at the slave cemetery. We could not stay as the Mansion Tour was starting.

If you have read this far I am sure you can tell that I found this tour to be deeply troubling. When I signed up for the tour, what I had hoped for was information that would truly give an insight to what slave life on the plantation was like. Rather than taking us through the working gardens, the various outbuildings where the slaves worked, we were led through 2 bunk houses that would have housed no more than 10 slaves each. As previously mentioned there were upwards of 300 slaves living on the plantation at any given time. The area which housed the majority of the slaves consisted of wooden shacks which, according to our guide became dilapidated and were torn down over time. In their stead, an office building for the Mount Vernon staff was built.

The whole tour seemed to whitewash the issue of slavery. At the end of the tour I didn’t come away with any increased understanding.

I was troubled by the use of the term “enslaved” to referred to slaves. It seemed like an attempt to lessen the impact of the subject. I also noticed that the tour guide for the Park Service (who was also black) at the Lee Mansion in Arlington Cemetery also used the term enslaved, but not as often as the guide Mount Vernon did.

Was the use of the term enslaved intentionally done to lessen the harshness of the issue of slavery? Or was it an attempt to be more inclusive as to include the indentured white Europeans who were enslaved during this time as well? I don’t know, and I could not get an answer to that. But it seems to me that if you’re going to talk about a group of black Africans who were brought to this country to work as slaves then you need to talk about those people as slaves and not try to make it seem not so bad by referring to them as enslaved people.

And if you want to talk about the white Europeans who came to this country as indentured servants who were required to work off their indenture before they could become free, then you need to talk about those people separately and make it clear which group you are referring to.

Honestly, I fully well expected our tour guide at Mount Vernon at some point to turn to us and say, “all lives matter.”

Are we right to feel uneasy and embarrassed around the issue of slavery in our country? Of course we are. But we need to confront it directly and head on, to deal with it openly and honestly, without trying to put some happy veneer on the subject.

My purpose here is not to try and cast, or to suggest, Washington was a harsh master. He was a product of his times, and if we are to believe what the history books tell us, he indeed did have problems with the issue of slavery, and failing to do more to end it during his lifetime may truly have been one of his lifetime regrets. If so then why did he wait until 5 years after his death, through his will, to release his slaves? Was it to give his heirs time to plan for their management of the plantation after his death? Was it to give them time to purchase their own slaves to run the plantation? We will never know the answers to these questions.

What I would say to the ladies of Mount Vernon Association is this: you have done a marvelous job at preserving and restoring the estate of George Washington in all its glory. Everyone believes he was one of the great leaders of his time. If you’re going to offer tours to give the public information about what slave life on the plantation was like, then do an honest job with it. Peel off the veneer, give us some real information, and address the subject honestly, or change the name of the enslaved peoples tour to the “George Washington wasn’t really that bad to his slaves tour.”

In case you were wondering . . .