Forget “The Biden Rule”, what Abraham Lincoln did, what Lindsey Graham said about waiting if a vacancy occurred after the primaries started, or McConnell’s “rule” about the people pick the president, blah, blah, blah. This is not tennis. There is no net. This is politics. There are no rules beyond what the Constitution says, and it says the president shall nominate and the Senate shall appoint. Period. Republicans rule the Senate. This nomination is going to happen before the end of the term, and there’s NOTHING the democrats can do to stop it. So don’t get wrapped up in sending in donations to political groups to stop the process. JUST VOTE. We can’t stop this, but we can oust the orange bastard and take back the Senate. Stopping this nomination and appointment is, I’m afraid, a lost cause.

Article II, Section 2 of the United States Constitution states: “[The president] . . . shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint . . . Judges of the supreme Court . . ..” End of story. There’s nothing there about vacancies occurring near elections, who controls the White House and/or the Senate. All that is superfluous.

This is the THIRD time. Everyone on the left gets all hysterical, a few republican senators prattle on about their disgust and give indications that they may vote against the tyrant, and … then … they … fall … in … line. This time won’t be any different. I promise.

But there was a time, four years ago, when the Democrats or any minority party for that matter, could have stopped a Supreme Court nomination. That ended in the first year of Trump’s presidency when the Senate employed the “nuclear option” to do away with the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations. If the filibuster had been in place a minority of the Senators, 41, could have blocked the nomination. Democrats could have easily prevented ANY of Trump’s three Supreme Court nominees. In Trump’s first term, Democrats, were still pissed that McConnell and the Republican Senate had, for 10 months refused to even hold hearings on President Obama’s nomination of Merrick Garland to replace the late Antonin Scalia on the basis that the President was in the final year of his second term and that the new president should be allowed to select the new justice. Wikipedia records the fiasco thus:

Political commentators at the time widely recognized Scalia as one of the most conservative members of the Court, and noted that—while many considered Merrick Garland a centrist, and he had been called “essentially the model, neutral judge”[8]—a replacement less conservative than Scalia could have shifted the Court’s ideological balance for many years into the future. The confirmation of Garland would have given Democratic appointees a majority on the Supreme Court for the first time since the 1970 confirmation of Harry Blackmun.[9]

The 11 members of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s Republican majority refused to conduct the hearings necessary to advance the vote to the Senate at large, and Garland’s nomination expired on January 3, 2017, with the end of the 114th Congress, 293 days after it had been submitted to the Senate.[10] This marked the first time since the Civil War that a nominee whose nomination had not been withdrawn had failed to receive consideration for an open seat on the Court.[11] Obama’s successor, Donald Trump (a Republican), nominated Judge Neil Gorsuch to fill the vacancy on January 31, 2017, soon after taking office.[10]

Democrats were set to block the appointment of Neil Gorsuch using the filibuster. McConnell knew it and so did the president.

Republicans controlled the Senate by a 53 to 46 majority (plus one independent, Bernie Sanders, who caucused with Democrats), easily enough votes to confirm any nomination on a straight up majority vote, which is normally required by Senate rules. If enough Senators were unhappy with a nomination, the minority, 41, could invoke the filibuster which would allow for unlimited debate on the floor of the Senate until 60 Senators could be put together to end the process through what is called “cloture.” To avoid or end a filibuster, a president would usually withdraw the nomination and nominate a more palatable candidate to the Court, thereby assuring that no one who was too right or too left leaning would be appointed. For a full discussion of FILIBUSTER, CLOTURE AND THE NUCLEAR OPTION.

In that case, the President and McConnell invoked the “nuclear option”, see above, doing away with the filibuster and allowing a majority vote to appoint Supreme Court nominees. The result for the administration has proved spectacular for the right wing with what promises to be THREE ultra right-wing justices sitting on the Court, tilting the political spectrum to to right for decades to come.

A couple of weeks ago before the nomination of Amy Coney Barrett to fill Ginsberg’s seat, the New York Times, in their morning newsletter, This Morning, summarized the struggles of the parties (mostly Democrats) to appoint justices. The portion which is reproduced below is unedited and complete with internal links.

Surrendered Court Seats

In the final decades of the 20th century, liberals and conservatives each had their own problem that kept their preferred judges from dominating the Supreme Court.For conservatives, it was the unreliability of the justices appointed by Republican presidents. Some turned into relative moderates (Sandra Day O’Connor and Anthony Kennedy), while others drifted further left (David Souter, John Paul Stevens and Harry Blackmun).

For liberals, the problem was the mishandling of Supreme Court transitions, through the occasional surrendering of a seat so that a Republican president could fill it.In 1968, the last year of Lyndon Johnson’s presidency, he appointed a personal friend to replace the departing chief justice — and when the nomination floundered on ethical grounds, the seat remained available for the next president, Richard Nixon, to fill. Later, two other liberal justices — Hugo Black, in 1971, and Thurgood Marshall, in 1991 — retired under Republican presidents and were each replaced by a conservative justice. Marshall’s replacement, Clarence Thomas, is still on the court today.

If you want to understand why conservatives have come to dominate the court in the early 21st century, it’s worth keeping in mind this history. In the simplest terms, conservatives have largely solved their 20th-century problem: Republican presidents now nominate only deeply conservative justices. Liberals, on the other hand, have not solved their problem.

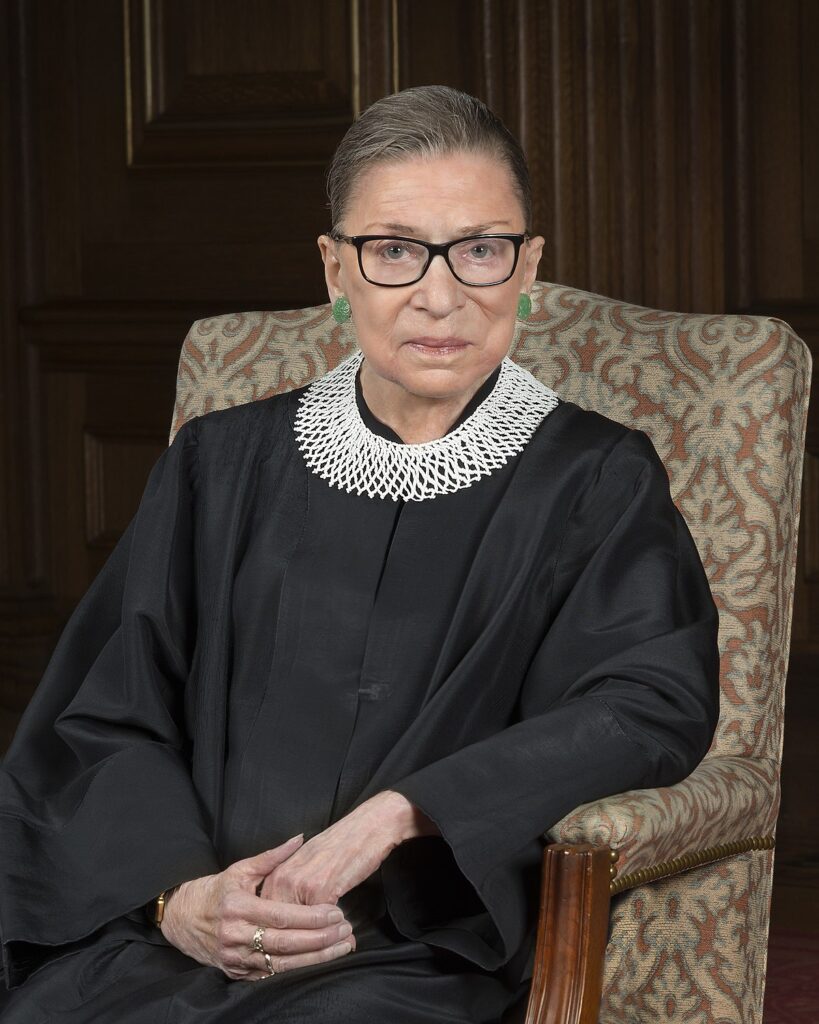

The death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg — like Marshall, a civil rights giant, who demanded that the United States live up to its ideals — has created the fourth time in the last six decades that liberals may turn over a seat to conservatives. Aware of this possibility, some legal scholars and writers pleaded with Ginsburg to retire while Barack Obama was president and Democrats still controlled the Senate, but she wanted to remain on the court.

President Trump and a Republican-controlled Senate now have the opportunity to place a sixth conservative member on the nine-member court. The new justice would likely be a young one who could remain there for decades, potentially helping overturn Obamacare and Roe v. Wade, outlaw affirmative action and throw out climate legislation.

The bungled Supreme Court transitions by liberals obviously aren’t the only reason that conservatives control the court. The unpredictable timing of death plays a role. So did Senator Mitch McConnell’s unprecedented refusal to allow Obama to appoint a justice following the 2016 death of Antonin Scalia. The Electoral College’s bias toward Republicans — allowing Trump and George W. Bush to become president despite losing the popular vote — matters, too.

Yet the flipping of seats from one ideology to another has been crucial. The effect of each instance can last for decades, well beyond any individual justice’s tenure, because each one can try to time his or her retirement to line up with the tenure of an ideologically similar president.

Earl Warren, the liberal chief justice for most of the 1950s and ’60s, understood this and deliberately announced his retirement in 1968, knowing he did not have long to serve on the court and fearing that Nixon would win election later that year. After Johnson failed to replace Warren, that’s precisely what happened.

Nixon’s choice, Warren Burger, was a conservative who helped undo some of Warren’s legacy. The next two chief justices, William Rehnquist and John Roberts, were also deeply conservative. Fifty-two years after Johnson mismanaged Warren’s retirement, the chief justice’s job is still in conservative hands.

If Trump replaces Ginsburg, the effect could be similarly long-lasting. The political battles of the next few months — both the court fight and the election — are about as consequential as American politics get.

So, there you have it. “Welcome” to the bench, Justice Amy Coney Barrett. Whether you like it or not.

In case you were wondering . . .

*With thanks to Herman’s Hermits and the unknown lyricist of The Cow Kicked Nelly in the Belly, paraphrased.